The Samara Project Slated for October Launch

To preserve the legacy of Todd Samara, a nationally recognized artist whose favorite subject was Kingston’s Rondout, a group of Kingston artists have formed the Samara Project, which is proposing a month-long, city-wide retrospective of Todd’s work this October.

The retrospective, which is sponsored by MAD, would include exhibits of Todd’s paintings at Kingston galleries, businesses and pop-up spaces curated by Chris Gonyea. A map of the month-long exhibits would also list the venues that have murals and other permanent displays of Todd’s colorful work, including the Hudson River Maritime Museum, Dolce and Tony’s Pizzeria. Also planned for October is an auction of Todd’s artwork, with the proceeds funding an arts scholarship to be awarded to talented local students.

Samara, who lived on a boat at the Hideaway Marina before settling in a house on Hone Street, was extremely prolific. Many of his fauve-like works were purchased by local collectors, while others are now being stored by his family and a local artist and friend since the artist, who requires nursing care, had to leave his home.

How The Samara Project Was Conceived

The Samara Project was launched after a group of Todd’s friends conferred with Todd’s brother Tom Samara, who informed them that the family wanted paintings from Todd’s estate to be exhibited and sold. Todd is on Medicaid, and Tom, who has power of attorney for Todd, said that if any profits from the sale of Todd’s paintings were to go to Todd, he would lose his Medicaid coverage, which is paying for his care. Therefore it was decided the profits would go towards an art scholarship or some other charitable cause.

The friends and volunteers who launched The Samara Project have the sole aim of raising awareness about Todd’s art in the community through a series of exhibitions, including works on loan from his collectors: They also hope to find homes for the approximately 300 works that are in temporary storage. Tom explained that in his current mental state, Todd does not understand the repercussions of this.

The volunteers of The Samara Project are dedicating their time and energy to organizing and curating a city-wide exhibition of his works as well as sharing stories about an artist whose life and practice enriched the local cultural scene. Cataloging and organizing Todd’s works for the auction that will occur at the end of the exhibition is a labor of love undertaken by his friends with no financial benefit to themselves. The sole motive of The Samara Project is to celebrate the work of this amazing and much beloved Kingston artist.

MAD is seeking volunteers to participate in and/or work with a steering committee to help organize the October event, which includes the following: working with venues to organize the shows of Todd’s work, doing publicity (including a possible insert that would run in the Almanac Weekly), preparing for the auction, and soliciting sponsorships from local businesses and individuals.

If you would like to help, please contact MAD by email. The organizers of The Samara Project will be meeting this month to come up with a budget and hammer out details of the proposed August celebration.

Todd Samara marched to the beat of a different drummer, eschewing such conveniences as a car and dedicating his life to his art. Below the photos is an article about the artist by Lynn Woods published in the Almanac Weekly in 2013.

“Painting never dies. It just keeps moving. You get past the madness and through the training of meditation, see the truth of the universe.” –Todd Samara

Click any photo to start a slideshow.

Todd Samara/Kingston Times

by Lynn Woods

May 14, 2013

Some places are inextricably linked with the artists who painted them. Fin de siècle Paris will forever be linked to the Impressionists and especially, the paintings of Manet, the cornfields and orchards of Arles with Van Gogh, Mont Sainte-Victoire in southern France with Cezanne, Mount Fuji with Hokusai, and Depression-era Main Streets with the matter-of-fact paintings of Edward Hopper. Similarly, Kingston’s Rondout will forever be associated with the paintings of Todd Samara.

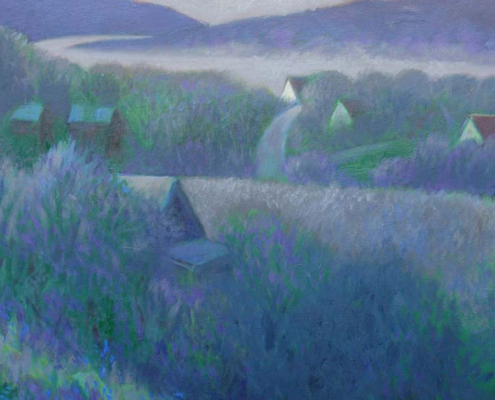

For 30 years, the 70-year-old artist has painted Rondout’s rows of gable-roofed houses, its panoramic river and mountain views, its boats, hilly streets, and people, doing the wash in laundry mats, hanging out in bars, playing in the schoolyards. Samara, who works from memory, has translated this subject matter into a language of simplified, textured forms and rich color, ranging from fauve-like intensity to subtle nuance; even his nocturnes glow with luminous blues and lavenders.

Anyone who knows Kingston knows a Samara when they see it. His murals adorn various corners of the city and his paintings are on more or less permanent display at Half Moon Books and Hudson Coffee Traders Uptown and Mint and Dolce in the Rondout. His style is distinctive, yet, when I sat down in the rotunda of the Hudson Coffee Traders earlier this week, it took me a moment to recognize the paintings surrounding me as his work, due to their starkness. They were radically simplified: like Giorgio Morandi’s bottles, houses have been reduced to their bare, geometric essence, as color shapes, accented with perhaps a single window. A scene is reduced to a few buildings, a patch of sky, and a shadow, with the contrasts in some paintings intensified. The paintings are devoid of people, heightening the sense of interiority and evoking primal states of emotion.

“Less is more,” said Samara, in a recent interview at his cozy Rondout home, which still contains its 1950s kitchen appliances. “I’m playing with colors and shapes. Each triangle or square connects to the one next to it. Maybe they’re on the same plane; you can’t always tell the background from the foreground. I’m playing with metaphysics. I’m trying to meditate and maintain the focus by thinking of no thing. I’m leery of that impressionist thing, which has way too many things going on at once. It’s like entertainment. Now I’m trying to be less romantic, for a certain quietness.”

Samara works out of a small studio in the basement of his 19th-century house. He also paints in his bedroom: When he wakes up in the morning, the first thing he does is to scoot over to a small table near his bed in a castor-wheeled stool and make one or two pictures on paper using cray-pas. “I don’t think,” he said. “It’s very spontaneous.” He then scoots over to another table and works on a small acrylic painting—or, as he has been doing of late, to a third table where he works on small panoramas using a brush dipped in ink. Sometimes he’ll put a bunch of these small works on paper in a folder and go down to Gallo Park, where he’ll sell them to passers-by for $10 or $20. His paintings and the ceramic works of Leslie Miller, his late partner, cover the walls, and more paintings are stacked against walls and piled up in corners.

Samara received national recognition when he was featured in the July-August 2010 issue of American Artist Magazine. The article came about after the writer discovered Samara’s paintings hanging in Dolce while on a visit to Kingston. The article sparked inquiries on his website, which his sister manages for him (he doesn’t have a computer). Though he was glad for the coverage and definitely would like to sell more paintings, which he relies on to pay his rent, supplemented by odd jobs and helping out a carpenter artist friend, he has no inclination to show his work outside of the area. Samara doesn’t drive, and he likes to keep things simple. When the owner of the house next door, where he and Miller were living in an apartment, offered to sell them the building for $10,000, Samara declined. “I don’t want to own anything. I hear about the problems from those who do.”

Samara has always marched to the beat of a different drummer. “I was against the rules because I couldn’t follow them,” he said, noting he rebelled against authority while growing up in Queens. Lately, though, he’s been going against his instincts. He’s taking lessons on the clarinet and learning to read music. “I’m breaking through that wall so I can create any feeling I want,” he said. Why clarinet? “It’s a romantic thing. I grew up hearing the clarinet. My parents were great dancers and went out every night. Music is like meditation. It puts you in another space. It’s like painting, in that I’m trying to put the feeling down.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1943, Samara made his first painting when he was 14, using the easel and paints of his father, a printer and frustrated artist. His father also introduced him to jazz and alcohol, taking his son to the Five Spot in lower Manhattan, where Dave Brubeck and other greats played. Samara has a photographic memory for images—he can look at something and then paint it from his head—but that didn’t help much in school, where he had trouble reading due to his dyslexia. “I was a cute red-headed kid with freckles, and the teachers felt sorry for me, so they kept passing me with 65s,” he recalled. He worked at Orbach’s, a clothing store across from the Empire State Building, instead of going to school some days as part of a special work/study program.

After graduating from high school he joined the Navy as a reservist and served on an aircraft carrier, traveling to the Caribbean and Europe. His first job was parking the planes, but “I was such a klutz, always banging myself on the wings, that they put me in the gear locker room,” where he handed out the tools. One day he found a big piece of wood and some red and white lead paint and painted the nude bust of a woman. Everyone liked it, and he started doing sketches and paintings based on photographs for the other sailors. He painted all the insignias and a large sign that read “Accidents do not happen, they are caused.” After he painted a mural of Moby Dick in the officer’s lobby, Samara enjoyed generous leave privileges when the boat was in port, hanging out in bars.

He quit the Navy in 1969 and moved back to Queens, renting two storefronts for $200 a month, which served as his studio, art gallery, and crash pad. He sold some work and attracted five students, “bored housewives who came over with a jug of wine and cheese. We discussed the arts.”

One day a couple came in who “clued me into Salvador Dali.” When they moved to Rocky Point, Long Island, where they opened an art gallery, Samara followed, renting space in the gallery and working as a bartender in the bar next door. After hitchhiking up to Rosendale to visit a friend who was living at Mohonk, Samara left Long Island for the former cement manufacturing town and worked as a bartender at The Well. His work at the time was influenced by the Mexican muralists and Cubism. He painted a handsome mural on the façade with curling flowers and a portrait of the bar’s owner, Uncle Willie, wearing a crown and cloak. He painted portraits of the ragamuffin clientele, who lived upstairs or in the nearby Astoria Hotel. One stoned-out patron freaked out upon viewing his portrait, which depicted his rolling, frenetic eyes and onyx necklace. “My client said ‘I see death’ and became a Christian because of the painting,” Samara recalled.

A friend convinced Samara to enroll at SUNY-New Paltz. However, “they wouldn’t let me in because of my low high-school average” even though he was an accomplished artist. Based on the mistaken impression by an administrator that Samara was Japanese in a phone conversation, he was nonetheless accepted into a special Educational Opportunity Program designed for minorities. Between the monthly subsidy he received in that program and grant money, “I made a few thousand a year,” which was sheer profit since he didn’t pay for housing, living in the free studio provided by the school. It was against the rules, but when a security guard broke in one night and discovered Samara living there, the artist convinced him to let him stay. “I said, ‘I’m a crazy artist and can only paint at night.’” Eventually bought a wooden dory for $200 and lived on it in Eddyville, hitchhiking every day to New Paltz.

“I was 35 years old, and I thought I could probably stay there the rest of my life,” he said. But all good things must pass, and after five years Samara graduated with a BFA. He had some good art teachers, especially one professor who helped him “look at everything as if it were alive.”

He bought a steel-hulled boat and lived at the Hideaway Marina for five years, where he worked, migrating to a shack on the property in the cold winter months. After meeting Miller in 2001, the two moved into a series of apartments, eventually ending up in the house where he lives now. Miller was diagnosed with cancer in 2004, which seemed to be cured after surgery but then returned. She spent time at home reading and writing poetry and did exhaustive Internet searches of alternative treatments. It was a difficult time. One day in 2004, “I bought a quart of Budweiser and a pack of cigarettes and knew I had to make a decision to go or stay,” Samara said. After that, he never drank or smoked again. “I know if I had stayed that way I would have killed myself. I was never addicted, but I couldn’t afford to do it and didn’t like all the rules. I kind of missed the madness of it all. But my attitude changed. I was not so upset as before.”

He and Miller started going to weekly qi dong classes at Benedictine, which Samara still attends. Stylistically, his paintings became darker, more somber. Miller died in 2009. The sign with both of their names still hangs near the front door, and her ceramic plates, sculpture and painted furniture maintains her presence in the house.

Having completed the series of austere, abstracted paintings for Hudson Coffee Traders, which will be on view through June, Samara said his style is shifting again, back to an energetic, impressionistic stroke. “I’m adding texture,” he said. “Painting never dies. It just keeps moving. You get past the madness and through the training of meditation, see the truth of the universe.”